Diversity and Pay Equity

It is now common practice in all companies to compare where we stand in terms of remuneration by age, gender and comparable professions. We consider it standard to have a fair playing field, and saying that we reward men and women equally is already part of good manners. But that doesn’t say that we treat men and women fairly at all. It’s just saying that, at any given time, that’s how our reward system is set up. We’re not saying anything about opportunity and historical development. So how do we find out how we are doing so that we can say that we are treating everyone equally?

The issue of diversity and equality is generally much more complex than the simple answer of whether we pay roughly the same for the same position. It just goes to show that pay policy works and does not take into account whether a man or a woman is being evaluated. There, only roles are taken into account.

When pay policy is set up well, there is not even a way to skew pay significantly in favour of the individual. And that’s okay because internal equity] is one of the most important components of a good company culture.

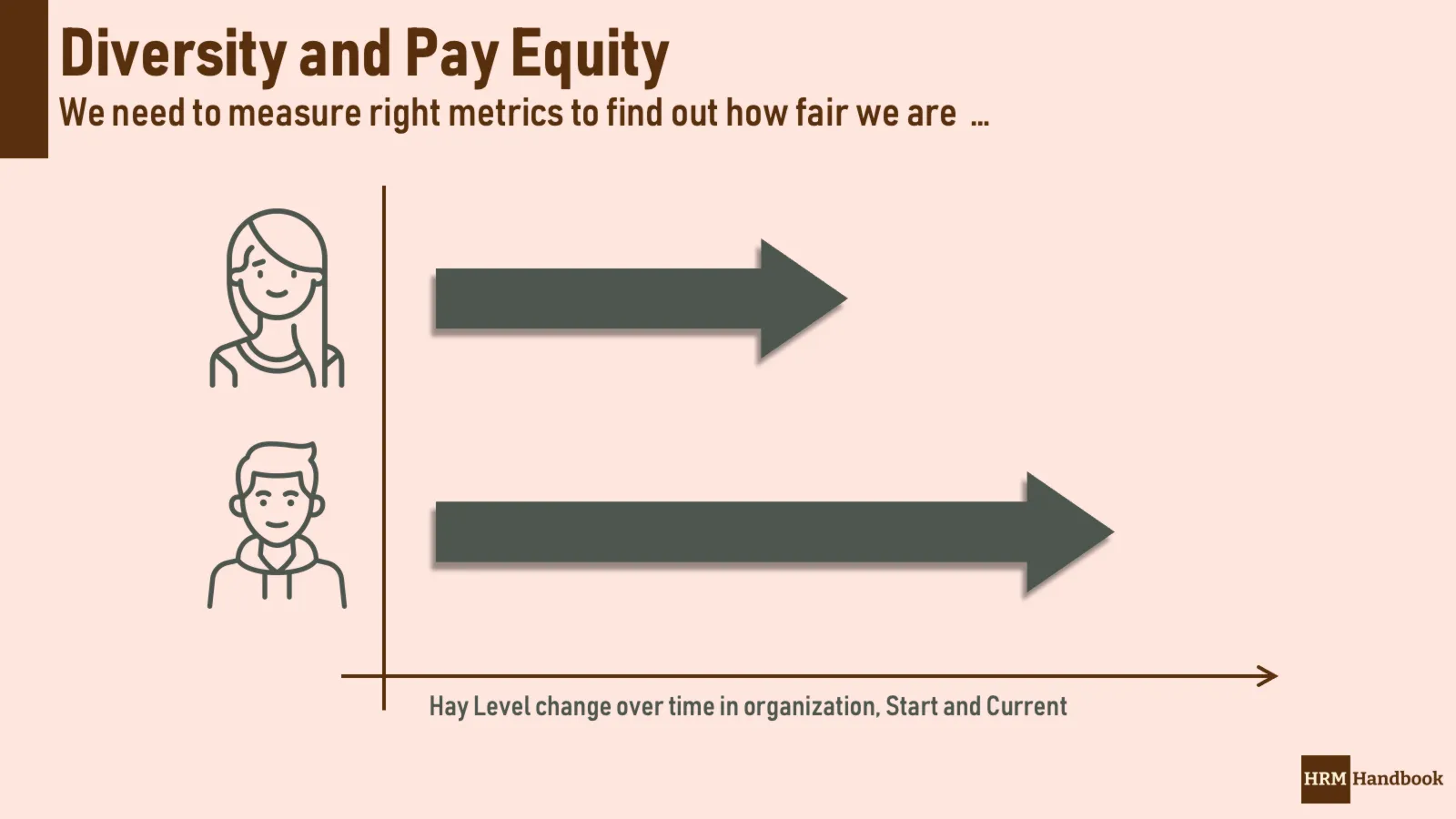

Only, then there’s the critical question. If we look at a group of employees who joined the organization at roughly the same point in time, how far have they come in that time. How their job classification has changed and how their pay has changed, we start to find some pretty fundamental differences.

And we start to see quite clearly that in most companies, women as a whole start to fall well behind their male counterparts. They are not promoted to more responsible roles as often and their pay is lower than men. And how is this possible? After all, we have a remuneration policy and we don’t look at gender in promotions. So how can this happen?

The answer comes from the side from which we would rather expect our social generosity. We have too much maternity and parental leave. We expect the mother to be at home with the child for two to three years. Whoever comes back first is the raven mother.

Only, in that time, she’ll lose two regular pay review cycles. She’ll get a lot of experience with time management, priorities, etc., but she’ll be out of the business and the company won’t appreciate that. Plus, he needs more time flexibility and that’s generally a problem. After all, a manager is expected to be fully loyal and available almost 24 hours a day.

And then there’s also issues of dynamics. After three years, you are returning to a company that is completely different. The social network is usually properly fluffy and you have to start proving from the beginning that you can and do. Again, you lose some time. At a critical time you often need to prioritise family and no woman will be there long to decide who takes priority.

In general, I think the issue of the English setting of motherhood and support in child rearing is an area that deserves longer examination and tons of remedial steps. Because the approach of locking her up at home for three years, calling it a vacation, and asking what else she seems to want isn’t yielding the results we expect.

We probably need to change more than just one pay policy. And to think especially about women who are not programmatically after a career, but just want that normal, fulfilling life.